So, what do artists do all day? I’ll give you a snapshot into this morning…

Today I discover that an experiment I made in backing a pair of prints with a sheet of paper to unite them flat for framing has sort of worked. Sadly the bit that hasn’t is quite important: the prints are desirably flat, but the backing paper is now tightly bonded to the glass sheet I used to support the experiment.

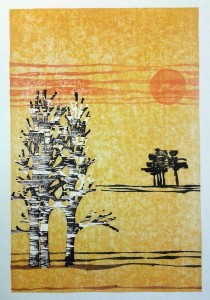

This is a bad thing, but not insurmountable. True these are finished prints and they are now stuck fast to the wrong thing, but they are Japanese woodblock prints. This means I can sit at the kitchen table with a bath sponge and a bowl of water and dab them until the whole thing is wet enough for me to release. Japanese watercolour and rice prints look delicate, but take damping and re-damping with the insouciance of the British at a bank holiday barbeque. I have two more sets of prints to go and another avenue of mounting needs exploring.

I learned the art of backing prints with supporting paper while on residency in Japan. Imagine the scene: a big room empty but for tatami mats and sliding paper screens, Mount Fuji at the end of the garden and students kneeling attentively (this does not include me. I cannot kneel and used to carry a note excusing me from kneeling in infant school. I stand respectfully instead). What the master says makes absolute sense and we accordingly mount and back prints successfully. What doesn’t translate, once I am in my own kitchen, is the access to the right brushes and papers. Here I am lacking in wide hemp, rabbit and deer hair brushes and the easy availability of washi paper. My prints are on European paper and I have emulsion brushes from the builder’s merchants. It’s now a question of adapt or fail.

This time I decide that the glass is best lined with cling film to prevent the backing sheet from sticking. I have seen Masterchef: I know cling film has diverse uses. First I wash the big sheet of picture glass in the bath to remove the last batch of gummed paper. As the glass slips around, I consider the health and safety forms I’ve just filled in for a class I have to teach. They require me to warn students not to trip over their own belongings. Nowhere do they cover the stupidity of juggling large sheets of thin, wet glass in a hard, curved bath.

I and the glass survive. Lining with cling film goes well, but then I worry the gummed tape to stretch the paper won’t stick so resolve to cut the film to the size of the paper to expose glass to the tape. For some reason I choose to use a meat cleaver for this (I am in the kitchen after all). More suited for a father intent on discouraging his daughter’s admirers, it actually works a treat and I am able to put fresh paper onto the film on the glass, damp and stretch.

The prints need to be stuck down with rice glue. I’ve made the glue by beating the hell out of a stiff rice and water paste for a full half hour over high heat while wondering if this is for the glue’s improvement or mine. Traditionally the resulting rubber ball is then diluted again by working with a hemp brush. I use the milkshake option on the blender. The cat appears and walks about on the prints. I shut him out. He swings on the door handle and yells, so I stop and place a chair in the sun where he agrees to sit and assumes the expression of Prince Phillip watching some not-so-good tribal dancing. I coat the back of my second batch of damp prints with the rice glue and offer them up to my scrupulously drawn guide lines more in hope than expectation. When they were handing out accuracy, I veered off course into the queue for creativity. I do my best, seal everything down and leave with the cat to dry in the warm.

It’s not yet nine am. This is a pretty normal day for me and I suspect for a lot of you creative people. It’s what we do and, though it’d be nice if things ran to plan, I do like a job that keeps me on my toes…