I’m often asked about my sketches and how I turn my ideas into a finished print. I always feel a bit awkward about this (it’s uncomfortably close to the ‘what music do you like?’ question which I dreaded as a teenage devotee of voice radio). For me, it’s a vague process at best; leaping from a few pencil lines to the full size template drawing for the block with nothing in between. Like most worriers, I suspect there is a party going on in the next room where artists in the know have exquisitely pleasing sketch books with annotations, fold out bits and delightful little objet trouve. Somehow my works on crime novel and thriller fly page seem sketchy beyond the point of sketchy, but they work for me and will make for an uber-cool retrospective if they haven’t gone off to Oxfam for re-reading.

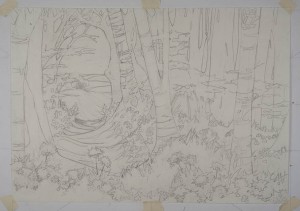

The drawing and planning comes with the print sized template drawing. These days all my drawing is done in outline with no colour. I only shade for planning purposes, not visual effect.

The upshot is more blueprint than charm and I simply draw, erase, draw until I am happy. I tend not to make more than one drawing, unless I am trashing it for a new start, as multiple efforts quickly lose their life and freshness. Since I arrive at my shapes by scribbling and then refining, the result is ‘architect meets infant scholar’. Neat drawing, but the paper a lumpy mess of rub outs and corrections.

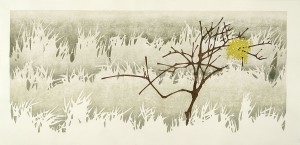

I do proof my woodblocks. Below you can see the proof for ‘Chiltern Seasons: Winter’ and play the spot the difference game with the final finished print.

See how many blocks I’ve cut and then discarded. Less is often more and I discard blocks and simplify the print far more often than I cut extra ones. The colours too are very different as you can see, though I never make rigid colour plans for either proof or edition, I just see the proof problems and address them as I go along. Proofing is also a chance to see if the blocks line up correctly and, if they don’t, it’s best to get the crying done over the cheap paper.

The journey from idea to print is different for every printmaker and I’m sure that there isn’t actually a rule book demanding a set route for the journey or means of travel. So I choose the Star Trek transporter method of arrival at finished work. Beam those prints up Scotty!